WHY QUEER THEATRE?

This post was originally published on the Buddies in Bad Times blog.

A few months ago, I wrote a blog post entitled Why Theatre? in which I outlined seven fundamental needs that I believe the theatre satiates in us. Today, I offer you seven reasons why I think queer theatre specifically is necessary and relevant to our society.

It celebrates difference

There is a section in Tawiah M’Carthy’s award-winning show Obaaberima where the lead character talks about how alienating it is to be a queer immigrant in this country. He describes how he had to erase his own culture and uniqueness and make himself as palatable and understandable as possible in order to participate in our society. As a young man from Ghana, he was denied the right to articulate and define his own story and identity.

Despite its best intentions, our society rarely nurtures differences amongst people. It prefers uniformity. Conformity. Predictability. Stability. One of the fundamental tenets of queerness is the belief that difference, whether it is sexual, cultural or religious, is actually good for society. It recognizes that the existence of difference (or, more importantly, the tension that difference creates) is a source for social innovation and renewal. The confrontation with difference pushes society forward.

Queer theatre defiantly presents perspectives that are alternative and unique. It stages stories and presents individuals that do not conform to normative narratives and identities. Queer theatre boldly says: “No, we are not all the same. Actually, we are kind of different from one another. And, not only is that okay, but it’s a good thing.”

It breaks down barriers

A few seasons ago, we toured a production of trans artist Nina Arsenault’s The Silicone Diaries which chronicled her extraordinary transition from male to silicone bombshell. One evening, after a performance in Ottawa, a tearful cisgendered heterosexual woman in her late 60’s approached me needing to “talk about what I just saw”. She found herself shocked by how much the show spoke to her own relationship to beauty and to the physical transitions that she was undergoing through aging. She said that she felt a level of connection to Nina’s story that she had never expected. It was an experience that was deeply healing for her and that forever altered many of her assumptions about trans people.

This is one the most exciting aspects of queer theatre. Yes, it celebrates difference but it also spurns the idea that there are fundamental and irreconcilable conflicts between people. It always assumes that people have the capacity to understand one another. And, it offers the possibility for some people to discover that the other is actually not so different after all. This is why queer theatre is a theatre of hope and optimism: its intent is to break down the barriers that isolate us from what is different and bring about greater empathy and connection within society.

It gives us permission to be ourselves

One of the more important notions within the concept of queerness is fluidity in our identities. It rejects the idea that one’s identity is singular, fixed, unchanging, and unchangeable. Queerness frees us from having to be consistent and coherent in our self-presentation and self-definition.

Queer theatre employs many devices to destabilize and subvert this limited understanding of identity such as camp, gender-fucking, drag, parody, sexual explicitness, nonlinearity, irony, exaggeration, surrealism, to name but a few. It reveals how identities can sometimes be total fabrications that have been imposed on us as a form of oppression. It acknowledges the ways that our identities change and evolve throughout our lives. It revels in the cracks and inconsistencies within our self-definitions. It empowers us to create and recreate ourselves. It pushes us to get beyond who we think we are supposed to be and discover the incredible vastness of who we can potentially become.

It protects our culture

Mainstream culture is a force that appropriates, depoliticizes, homogenizes, and neutralizes counter-culture. This cultural progression from fringe to mainstream is part of a larger political process that is always at play. It is a way for power structures to assimilate cultural currents that potentially threaten its position. Queer culture is currently undergoing this process.

Queer theatre is a resistance to this. It rejects a conception of equality that assumes that freedom is about minorities adapting to, and being accepted by, “straight/normal” society. It affirms that emancipation is not contingent on anyone adapting to the status quo and that a group’s worth should be measured on its own terms. Queer theatre is an empowering space for people to express and represent their own values and to enjoy their sense of worth without compromise. Queer theatre is a space for audiences to encounter the unfettered uniqueness and authenticity of those who might be different from them.

It gives voice to the dead

I am going to get esoteric for a moment. I remember reading a description of the theatre by UK playwright Howard Barker that I really loved. He describes the theatre as something that happens on the banks of the river Styx, which, in Greek mythology, separates the world of the living from the world of the dead. He places the audience on the side of the living. They sit looking at the dead on the other side of the river. The dead look back at the living with their mouths agape but they cannot utter any sound. On the river, in between the living and the dead, there is a boat. On this boat, there are the characters of a play. These characters are speaking the words of the dead to the living.

With this image, Barker suggests that the theatre is an art form that gives voice to the dead. As fictional beings, characters are not alive – but they are not exactly dead. Characters are conjured from a writer’s memory. Characters in plays occupy this liminal space in between life and death. They are created from historical records of “real” people. They are born from the poetic imagination. Characters are how the dead communicate with the living.

It actually turns out that this isn’t quite what Howard Barker describes.[1] But I like the way that I remember the image. Whether it’s the experience of sitting in the sobbing audience during The Normal Heart or feeling the electricity in the room during a performance of The Gay Heritage Project, I am constantly reminded that good theatre allows us to convene with the dead. What is particularly significant about queer theatre is that our dead, our history, and our memories have long been suppressed, silenced, and hidden.

It liberates the body

I read an account by Robert Mapplethorpe of his first time seeing a gay porn magazine as a young Catholic schoolboy. He spoke of how it impacted his body – the shortness of his breath, the tightness in his stomach, the hardening of his cock. It was the first time that his body overtook his mind. It was a complete awakening to a part of himself that he never knew existed. He said that, in this moment, he decided to be an artist and that he wanted his art to have this same effect.

One of the defining characteristics of systems of power in the western world has been the regulation of sexuality and the restriction of physical pleasure as a form of social control. If you can control what people’s bodies want, then you can pretty much control what these bodies do. And if there is one shared characteristic amongst queers is the decision to pursue one’s physical/sexual pleasure even when that pleasure runs counter to dominant social and moral values.

It is the privileging of the body – and, in particular, the various ways that the body can experience pleasure – that makes queerness subversive and disruptive. Lets not fool ourselves: despite the advancement of LGBT rights such as marriage equality, society is still fucked up about sex and remains profoundly distrustful of the body and physical pleasure. By putting sex at the centre of itself, queer theatre asserts our right to physical pleasure in all its forms.

It creates alternative communities

For the longest time, I operated under the misunderstanding that community was a noun. I believed “community” to be this thing that objectively existed in the world and that I could just access whenever I wanted. However, I have come to understand that community is actually a verb – it is a thing that you have to do. Without the action of coming together, there is no community to speak of.

Every night, inside our theatre, a community forms itself around a play. It is the act of coming to the play that brings the community into being. Sure, this is true of all theatre but what makes queer theatre extra-special is the kinds of communities that it creates. It allows communities to form around stories and ideas that are subversive, challenging, and alternative. It allows communities of people of who are underrepresented, invisible, and ignored to spring into being. By forming these communities, queer theatre provides a sense of belonging, solidarity, and strength to people who are often isolated and disempowered.

Concluding thoughts

Over twenty years ago, our founding Artistic Director Sky Gilbert wrote the following: “Let’s talk about Queer, because it doesn’t always mean gay or lesbian. It means sexual, radical, from another culture, non-linear, redefining form as well as content. […] you come into the theatre assured of who you are and what you believe, but you leave the theatre all shook up.”

In many ways, this still speaks to what makes queer theatre so essential to our culture. What I value most about the word queer is its potential to challenge the way we make meaning of the world. I believe that the term queer does not necessarily refer to a fixed identity but to a questioning stance that lets us explore the taken for granted and the familiar from new vantage points. Through queer theatre, we are able to form, deform and reform new shapes of identity that are more liberated, compassionate and multifaceted. Through queer theatre, we are to imagine a better world for everyone.

[1] This is what he actually writes: “Theatre is situated on the bank of the Styx (the side of the living). The actually dead cluster at the opposite side, begging to be recognized. What is it they have to tell? Their mouths gape…” Barker, Howard, “Death, the One, and the Art of the Theatre” p. 20

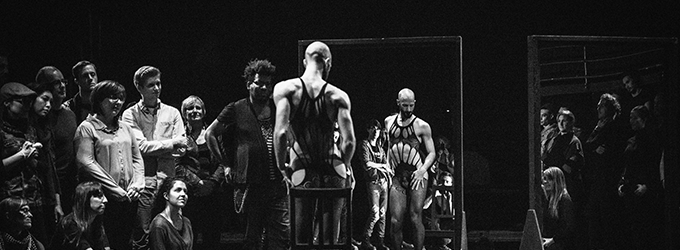

Images (from top): Ron Kennell & Diane D’Aquila in The Maids (Jeremy Minagh); Tawiah M’carthy in Obaaberima (Jeremy Mimnagh); Olive-or-Oliver at Friday Night Live (Alejandro Santiago); Gavin Crawford, Kyle Travis Young, Chy Ryan Span & Bruce Dow in Of a Monstrous Child: a gaga musical (Alejandro Santiago); Gerrard Reyes in The Principle of Pleasure, Rhubarb 2014 (Alejandro Santiago); David Ferry in Blasted (Omer Yukseker); India Davis at Strange Sisters 2013 (n maxwell lander); Gein Wong at Strange Sisters 2013 (n maxwell lander).

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.